In the field of industrial cutting, saw blades are often mistaken for ordinary consumables. However, for experienced engineers or production managers, a saw blade is a precisely designed instrument. The quality of the cutting effect often depends on a deviation of just two to three degrees in the tooth profile geometry, which can lead to severe fracture of the saw blade or result in a mirror-smooth cutting surface.

This time we dig into the physical traits of saw tooth angles, and breaks down how specific tooth shapes impact heat buildup, chip load and cutting quality for three main material types: ferrous metals (dry cutting), wood and architectural composites.

The Anatomy of the Tooth

Before analyzing specific applications, we must standardize our terminology regarding the three critical angular dimensions that define cutting performance.

The Rake Angle is the angle of the tooth face relative to a radial line drawn from the center of the blade to the tip of the tooth.

Function: It determines the "aggressiveness" of the cut. It dictates the shear plane angle—the angle at which the material is deformed and separated from the workpiece.

The Rule of Thumb: Higher positive angles require less power but produce a rougher finish and lower edge durability. Negative angles require more horsepower but offer superior control and edge strength.

The Clearance Angle (Relief Angle) —β

This is the bevel on the top of the tooth that’s away from the cutting edge.

Its job is to stop the carbide tips from rubbing against the material you just cut.

Here’s the trade-off: If the angle’s too steep, the tooth tips will be brittle and lack support, which leads to chipping. If it’s too shallow, friction will generate excessive heat, causing thermal expansion and eventually burning the workpiece.

The Radial (Side) Clearance

This angle tapers the tooth from front to back along the sides.

It cuts down on friction between the sides of the teeth and the walls of the kerf (the cutting slot). For dry-cutting jobs where there’s no lubricant to cool the tooth sides, this angle is super important for stopping heat from building up.

Ferrous Metals (The Dry Cut Cold Saw)

Focus: Thermal Management and Impact Resistance

Dry-cut cold saws (fitted with cermet or coated carbide tips) are the most technically demanding category to design. And here’s the counterintuitive goal: we want to generate heat, but we have to get rid of it right away.

During dry cutting, heat is generated by the plastic deformation of the steel. The tool’s geometry has to transfer about 80% to 90% of that heat to the chips—this way, both the blade and the workpiece stay cool. That’s exactly how the "cold cutting" principle works.

The Geometry of the "Cold Cut"

When cutting mild steel, we usually go with a three-chip grinding (TCG) profile. But the angle will vary depending on the microstructure of the steel.

Thin-Wall Applications (Tubing, Angle Iron, Channels)

Rake Angle: Positive (+5° to +10°)

Clearance Angle: 10° to $12°

Reasoning: A slightly higher clearance helps the tooth exit the cut cleanly without dragging on the burr typically formed on the inside of a tube.

Solid Applications (Bar Stock, Thick Plate)

Rake Angle: Zero to Low Positive 0° to +3°

The Physics: When cutting solid steel, the tooth engages with the material for a longer duration, creating a continuous, high-impact load. A sharp positive angle leaves the carbide tip unsupported and weak. A Zero Rake angle directs the cutting forces backward into the body of the blade, utilizing the compressive strength of the carbide (which is high) rather than its shear strength (which is lower).

Clearance Angle: 8°

Reasoning: A lower clearance angle adds more "meat" behind the cutting edge, acting as a heat sink and structural support.

Stainless Steel (The Work-Hardening Challenge)

-

Rake Angle: 0° to +5°

-

Special Consideration: Stainless steel (like SUS304) tends to "work harden" if rubbed. The blade must cut, not slide. While a zero rake gives strength, we often need a slightly larger Clearance Angle (12°) than used for mild steel. This ensures that after the cut is made, the back of the tooth does not contact the material, which effectively "springs back" slightly due to its elasticity.

Woodworking Applications

-

Focus: Grain Direction and Fiber Severing

Wood is an anisotropic material—its physical properties differ depending on the direction of the force relative to the grain. Therefore, saw blade geometry must adapt to the grain.

A. Ripping (Cutting With the Grain)

Ripping is essentially a chiseling operation. The goal is to lift long strands of fiber out of the way.

-

Rake Angle: High Positive (+20° to +25°)

-

Geometry: Flat Top Grind (FTG)

-

The Physics: The high hook angle acts like a hand plane, scooping out material rapidly. This aggressive angle pulls the wood into the blade. While this allows for very fast feed rates (vital for sawmills), it leaves a rough surface finish.

-

The Gullet Factor: The "Gullet" (the valley between teeth) must be deep and large. Long grain fibers create large volume chips; if the gullet is too small, the sawdust compresses, creating friction and burning the wood (and the blade).

B. Crosscutting (Cutting Across the Grain)

Crosscutting requires severing fibers that are perpendicular to the cut. If you use a ripping blade (FTG) here, it will "blow out" or splinter the wood on the exit side.

-

Rake Angle: Moderate Positive (+10° to +15°)

-

Geometry: Alternate Top Bevel (ATB) or Hi-ATB

-

The Physics: The teeth are beveled to form knife-like points on alternating sides. They score the fibers on the left and right of the kerf before removing the center material. The lower rake angle (10° vs 20°) slows down the "grab" of the blade, allowing for a smoother shearing action that leaves a polished end-grain.

-

Non-Ferrous and Composites

-

Focus: Safety and Abrasion Resistance

A. Aluminum and Non-Ferrous Metals

Aluminum is soft, ductile, and has a low melting point. It is notoriously "gummy" and tends to clog blade teeth.

-

Rake Angle: Negative (-5° to -6°)

-

Geometry: TCG

-

The Physics of Safety: If you use a positive hook angle (like a wood blade) on aluminum, the blade will "climb" onto the material. In a manual chop saw, this can violently pull the saw handle down or throw the workpiece. A Negative Rake angle changes the force vector: it pushes the material away from the blade and against the back fence, ensuring a safe, controlled cut.

-

Lubrication: Unlike steel dry cutting, aluminum usually requires mist lubrication to prevent the chips from welding to the gullet.

B. Construction Composites (Laminates, Melamine, Fiber Cement)

-

Rake Angle: Negative (-2° to -5°)

-

The Physics: Materials like Melamine have a brittle, glass-hard surface coating over a soft particleboard core. A positive hook lifts the material upward, causing the brittle surface to chip out. A Negative Hook presses the material downward during the cut, compressing the surface layer and preventing chipping.

-

Material Note: For fiber cement (highly abrasive silica content), the angle matters less than the tip material. Polycrystalline Diamond (PCD) tips are mandatory for longevity, typically featuring low positive angles (+5°) to manage the heavy dust load.

-

Post time: Dec-16-2025

TCT Saw Blade

TCT Saw Blade HERO Sizing Saw Blade

HERO Sizing Saw Blade HERO Panel Sizing Saw

HERO Panel Sizing Saw HERO Scoring Saw Blade

HERO Scoring Saw Blade HERO Solid Wood Saw Blade

HERO Solid Wood Saw Blade HERO Aluminum Saw

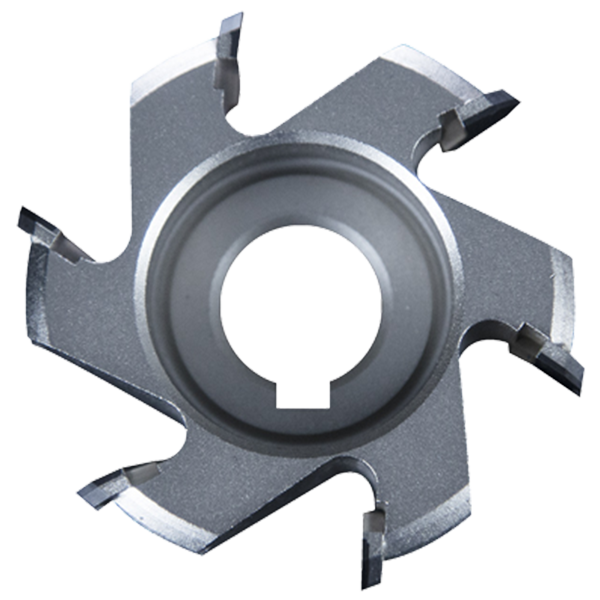

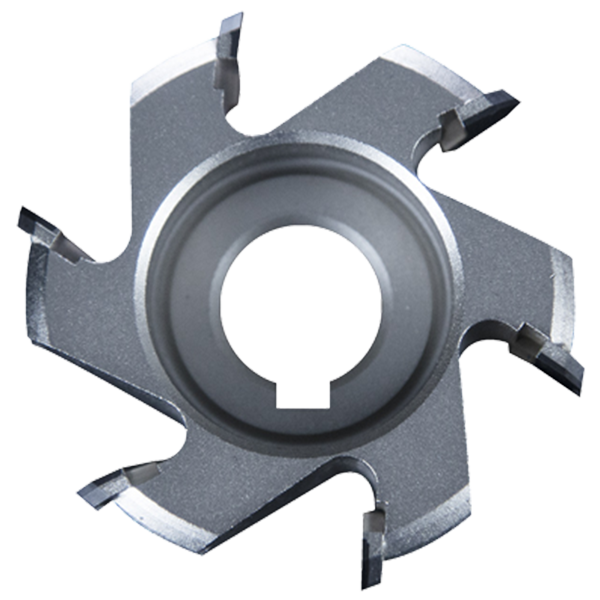

HERO Aluminum Saw Grooving Saw

Grooving Saw Steel Profile Saw

Steel Profile Saw Edge Bander Saw

Edge Bander Saw Acrylic Saw

Acrylic Saw PCD Saw Blade

PCD Saw Blade PCD Sizing Saw Blade

PCD Sizing Saw Blade PCD Panel Sizing Saw

PCD Panel Sizing Saw PCD Scoring Saw Blade

PCD Scoring Saw Blade PCD Grooving Saw

PCD Grooving Saw PCD Aluminum Saw

PCD Aluminum Saw Cold Saw for Metal

Cold Saw for Metal Cold Saw Blade for Ferrous Metal

Cold Saw Blade for Ferrous Metal Dry Cut Saw Blade for Ferrous Metal

Dry Cut Saw Blade for Ferrous Metal Cold Saw Machine

Cold Saw Machine Drill Bits

Drill Bits Dowel Drill Bits

Dowel Drill Bits Through Drill Bits

Through Drill Bits Hinge Drill Bits

Hinge Drill Bits TCT Step Drill Bits

TCT Step Drill Bits HSS Drill Bits/ Mortise Bits

HSS Drill Bits/ Mortise Bits Router Bits

Router Bits Straight Bits

Straight Bits Longer Straight Bits

Longer Straight Bits TCT Straight Bits

TCT Straight Bits M16 Straight Bits

M16 Straight Bits TCT X Straight Bits

TCT X Straight Bits 45 Degree Chamfer Bit

45 Degree Chamfer Bit Carving Bit

Carving Bit Corner Round Bit

Corner Round Bit PCD Router Bits

PCD Router Bits Edge Banding Tools

Edge Banding Tools TCT Fine Trimming Cutter

TCT Fine Trimming Cutter TCT Pre Milling Cutter

TCT Pre Milling Cutter Edge Bander Saw

Edge Bander Saw PCD Fine Trimming Cutter

PCD Fine Trimming Cutter PCD Pre Milling Cutter

PCD Pre Milling Cutter PCD Edge Bander Saw

PCD Edge Bander Saw Other Tools & Accessories

Other Tools & Accessories Drill Adapters

Drill Adapters Drill Chucks

Drill Chucks Diamond Sand Wheel

Diamond Sand Wheel Planer Knives

Planer Knives